When the Seattle Kraken joined the NHL, fans hoped for a smart, modern expansion team that could compete quickly. Five seasons later, the reality is starkly different: overpaid middling players, wasted cap space, and a roster that struggles to compete in a cap-driven league.

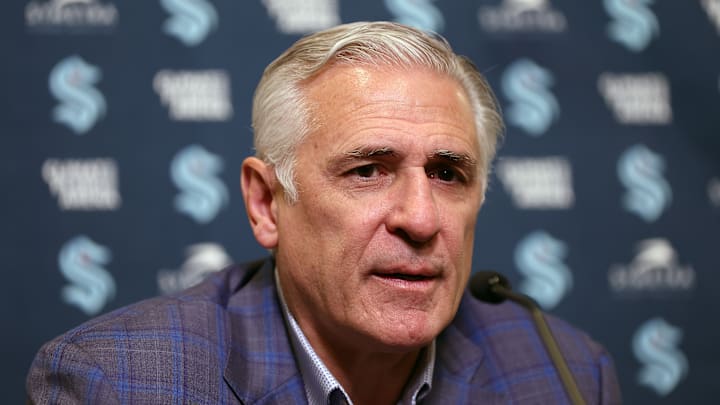

At the heart of it all is Ron Francis, whose contract decisions and failure to leverage Seattle’s unique advantages have left the Kraken stuck at the bottom.

The case for Francis

It would be unfair to paint Francis’s résumé as a total failure. He does have an eye for talent, and some of his moves have shown genuine value.

Seattle’s prospect pipeline has been bolstered by the additions of Matty Beniers and Shane Wright, giving the franchise at least some foundation to build on. Not only that but also Berkley Catton and Jake O’Brien, who have yet to see the ice at a professional level.

The expansion draft also brought in Vince Dunn, a player who represents the kind of winning culture Seattle desperately needed, and Joey Daccord an exceptional goalie.

Perhaps Francis’s best work came on the trade market, when he fleeced Columbus for Oliver Bjorkstrand in a deal that still looks lopsided today.

These moves show that Francis can find value when navigating trades and draft boards and that he isn’t blind to talent, but the positives stop there.

The contract problem

The real story of Francis’s Kraken tenure is defined by the contracts he signed.

Francis rushed into free agency and committed long-term money to a string of middle-tier players.

Alex Wennberg received three years at $13.5 million, a number that assumed he could be a second-line center despite producing like a depth forward.

Andre Burakovsky signed a 5 year $5.5 million AAV absolutely robbing the Kraken for his nonexistent production.

Francis invested $35.4 million into Philipp Grubauer who immediately imploded, posting sub-.900 save percentages and anchoring Seattle at the bottom of the standings.

Lastly, the most glaring of all, signing Chandler Stephenson to a 7-year, $43.75 million contract for a player who is not even close to being worth his price tag.

The common thread is clear. Francis consistently paid players as though they were impact pieces when, in reality, they were role players, and not good ones. By tying up the team’s cap space in these kinds of contracts, he limited Seattle’s flexibility and blocked the path to chasing true top-end talent.

The Carolina parallel

If this all sounds familiar, that’s because it is. Francis’s tenure in Carolina ended for many of the same reasons

In 2016, he handed Victor Rask a six-year, $24 million extension based on a single decent season. Rask’s production collapsed, and the deal became one of the ugliest on the books.

Around the same time, Francis made perhaps his most infamous move: acquiring Scott Darling and signing him to a four-year, $16.6 million deal to be Carolina’s starting goaltender.

Darling quickly fell apart, posting a .888 save percentage and becoming unplayable, leaving the Hurricanes stuck with an anchor contract, does this sound familiar?

Even smaller moves followed the same logic. He extended Eddie Lack before he had played a meaningful game in Carolina, committing money to a backup who never lived up to it.

Fast forward to Seattle, and the parallels are striking.

Wennberg was the new Rask: a center paid like a core piece but performing as a fringe one.

Grubauer is the new Darling: a supposed franchise goaltender signed long-term who has been a glaring weakness instead.

Gaudreau echoed the Lack mistake, committing money to a depth piece with little upside.

In both Raleigh and Seattle, Francis repeated the same approach: overpay middle-of-the-roster players, misjudge goaltenders, and avoid pursuing elite stars.

This isn’t a case of bad luck. It’s a philosophy, and it hasn’t worked twice now.

The no-state tax advantage - wasted

Seattle sits in one of the few states in the NHL without income tax, a built-in advantage that should make the Kraken more competitive.

Yet under Ron Francis, the team has failed to leverage this edge, leaving money on the table and inflating its roster costs unnecessarily.

The hidden advantage Seattle ignored

One of the most baffling aspects of Ron Francis’s tenure is how little he leveraged the Kraken’s biggest built-in advantage: Washington’s lack of state income tax.

Around the league, this factor has been the subject of heated debate, especially as fans watch teams like Florida and Tampa Bay build perennial contenders while enjoying the tax break.

In fact, of the last six Stanley Cup champions, five have come from states without an income tax: Vegas (once), Florida (twice), and Tampa (twice).

While the effect isn’t everything, as Dom Luszczyszyn outlined in The Athletic, it’s still a tool that smart management groups can weaponize.

Dom Luszczyszyn’s Numbers: Seattle overpaying

Luszczyszyn’s model examines contracts for skaters with a cap hit over $1 million, comparing what teams paid to the expected value of the player at the time of signing.

This isn’t about contracts aging poorly; it’s about efficiency at the moment the deal was made.

The results are stunning: Florida leads the league with an average $1 million discount per contract, while Seattle is dead last, paying a $1.3 million premium.

That overpay is not a trivial number, it directly impacts the Kraken’s flexibility under the salary cap and is a major reason the team struggled to maintain a full roster while finishing in the bottom six of the league last season.

Signing Bonuses: The missed opportunity

Where the Kraken failed is obvious when compared to other no-tax states.

Florida, Tampa, and Vegas rely heavily on signing bonuses to exploit their tax-free status.

Aleksander Barkov, for example, makes just $1 million in base salary, with the rest of his contract front-loaded into bonuses taxed only at Florida’s zero rate.

Tampa’s contracts are 51 percent bonuses, Vegas sits at 49 percent, and Florida leads the pack at 81 percent. Seattle? Just 9 percent of its contracts include signing bonuses, the lowest among no-tax states aside from Nashville’s 18 percent.

Even though Seattle has ownership willing to invest, facilities, AHL rosters, and more, the Kraken have largely ignored signing bonuses as a strategic tool.

The Stephenson Example: Blueprint ignored

Chandler Stephenson’s contract is a perfect example of a missed opportunity.

His Seattle deal includes just $4 million in signing bonuses in year one and $2 million in year three.

Imagine if Francis had structured it differently: Stephenson could have a $1 million base salary with $4 million in signing bonuses each year.

The official AAV would lower to $5 million, but Stephenson would take home the same or more, thanks to Washington’s no-tax advantage, and Seattle would pay about $1.25 million less in true cap cost per year.

That figure coincidentally aligns almost exactly with what the Kraken are overpaying across the roster.

The only downside, more complicated buyouts, is manageable, especially if the bonuses are front-loaded and not extended through the player’s entire contract.

The Theodore Model: How smart teams exploit bonuses

Vegas’s treatment of Shea Theodore provides the ultimate blueprint.

At 29, Theodore just signed a seven-year extension with massive signing bonuses in his prime: $8.5M in year one, $8.5M in year two, $7.6M in year three, and $6.3M in year four, after which the bonuses disappear as he hits 33.

This front-loaded approach maximizes the tax-free advantage while mitigating risk as the player ages, keeping the cap hit clean.

This is exactly the kind of creative contract structuring Seattle needed to adopt, front-load the bonuses in prime years, taper before decline, and leverage Washington’s tax-free environment.

Francis, however, never attempted it.

The cost of mismanagement

By ignoring signing bonuses, Francis forced Seattle to rely on inflated base salaries, creating the very $1.3 million per contract overpay Luszczyszyn identified.

The Kraken ended up capped out while still finishing in the league’s bottom six. This is not a matter of weather, reputation, or being a new franchise, teams in similar positions, from Vancouver to San Jose to Washington, manage far more efficiently.

As Luszczyszyn put it: “While it’s fair to say there is some advantage for teams in no-tax states, it’s not given — it’s one that needs to be extracted by a strong management group. This primarily comes from pricing.”

Seattle had the perfect opportunity to exploit a structural advantage few teams enjoy, and instead, Francis turned it into a liability. It’s not just bad luck, it’s bad management.

The Ripple Effect in Seattle

For the Kraken, the fallout has been severe. Instead of becoming the NHL’s next great expansion story like the Vegas Golden Knights, Seattle has been saddled with mediocrity.

The roster is filled with players who are good enough to compete but not good enough to win.

There’s no true face of the franchise beyond Matty Beniers, and no cap space to chase a legitimate superstar.

Fans have been left frustrated by a team with no clear identity and little hope of turning things around quickly.

The mistakes Francis made in Carolina weren’t corrected in Seattle, they were doubled down on.

Ron Francis’s legacy is now unmistakable

He is a general manager who can draft well and find the occasional trade win, but who repeatedly sinks his teams by misvaluing players in contract negotiations.

His philosophy has left two franchises, Carolina and Seattle, trapped in the same cycle: stuck with expensive, underperforming role players and without the elite talent needed to contend.

Sure, Carolina is good now, but you truly can’t attribute that to Ron Francis.

The Kraken were supposed to ride the wave of expansion momentum into something special.

Instead, thanks to Francis’s contract philosophy, they’re stuck treading water, and hopefully new GM Botterill can save us, if not, Seattle risks spending its early years defined not by success, but by squandered opportunity.

More from Kraken Chronicle